Westminster Forum event on gene editing

Leonie Nimmo reflects on problems and a paradox

In April, the Westminster Food & Nutrition Forum hosted a conference to discuss the next steps for gene editing—new GMOs—in the UK. The Genetic Technology (Precision Breeding) Regulations (GenTech Regulations) were making their way through parliament, and I attended to find out more about the perspectives of the government, industry and other organisations that were represented.

Our initial report about the meeting highlighted many of the issues raised—issues that we and others have long been reporting on—including the government’s refusal to label new GMOs, the likely disruptions in trade as a result of their deregulation in the UK, and contamination. This article further reflects on some issues and insights.

Image: Chris Cullen

Patronising the public

It was remarkable that Gideon Henderson, who was then Chief Scientific Advisor to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), used a discredited poll to make claims about public opinion in relation to new GMOs.

The Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee produced a damning report on the GenTech Regulations that drew particular attention to DEFRA’s refusal to publish the poll in question. However, its chair, Dr Mark Pack, used polling transparency rules to force its publication by the pollster YouGov. It turns out that only half of just 2,000 people surveyed had heard of genome/gene editing. They were also given positives about the technology and no possible concerns.

This approach, of telling people about the benefits of new GMOs without mentioning risks or disputed issues, was familiar to Duncan Ribbons of the biotech company Tropic Biosciences. He said it was hard to educate consumers from a scientific perspective, whereas issues framed in terms of benefits were more readily understood and accepted. Dr Fere Malekpour from Beehive Innovations also stressed the need for highlighting the benefits when talking to the public about the science.

But even DEFRA’s discredited poll that found that nearly half (43%) of the tiny sample polled didn’t support the use of new GMOs in food. Should this data really be used by DEFRA’s Chief Scientific Advisor to claim public support for new GMOs? One would hope that his analysis of scientific data is more robust than his interpretation of polls.

What rot!

Tropic Biosciences is based in Norwich but was co-founded by a former Israeli Navy ship commander and has a board chairman who is an advisor to the Israeli Prime Minister’s Office. Tropic has developed a non-browning banana that has received some positive attention in the British press for its claimed potential to reduce food waste.

Three examples of gene-edited fruit and vegetables were presented during the conference, and another of these had also been genetically modified to prevent discolouration: a non-bruising potato being developed by Beehive Innovations.

Both bruising and browning happen for a reason—they indicate that a fruit or vegetable has either been damaged or is not fresh. In both cases, the discolouration indicates that the food is rotting. In preventing the discolouration, do the genetic modifications also prevent decomposition? Or will they result in people eating rotting food that they would otherwise choose to avoid?

Either way, the technology could be of benefit to food manufacturers, who would be able to sell food that was not visibly decomposing, or not worry about the way food was handled because it would be more able to tolerate knocks. Thus, there will be more profit and less food waste—the only issue the mainstream media appears interested in highlighting in relation to such products. But the development of these traits may reflect where power lies in the food industry and what manufacturers want rather than any sustainability purpose.

I asked questions of both Duncan Ribbons from Tropic and Dr Fere Malekpour from Beehive in an attempt to clarify the relationships between the genetic modifications, the rotting process and the nutritional value of the fruit or vegetable. Ribbons claimed there would be no change to the nutritional value of the fruit if it was stopped from browning or bruising.

I asked Dr Malekpour if the potatoes she was developing would look nutritionally healthy even if they were bruised and less nutritious and the answer was” “Potentially, yes…”

However, the length of time after harvesting has a direct impact on the nutritional value of fruit. So, if I understood Ribbons’ answer correctly, a GM, non-browning banana that was sold an extended period of time after harvesting would have the same nutritional content as a visibly decaying conventional banana. It would therefore seem that the genetic modifications don’t prevent decomposition, only the appearance of decomposition. If so, I wonder how they would taste? And if not, what are the environmental implications of food that is not biodegradable?

Should anyone from Tropic or Beehive wish to confirm or clarify, we’d like to hear from them.

The patent paradox

The conference highlighted what is likely to become a major issue for the food production sector in the wake of the GenTech legislation: patents.

New GMOs—in the UK at least— are almost certain to be patented. It is supposedly not possible to patent purely biological processes, but this creates a logical inconsistency, because the definition of a “Precision Bred Organism” is that it could have been produced by a purely biological process––traditional breeding.

Patents on new GMOs have an impact on traditional breeding, because the traits that are developed can be patented and, if these can be achieved through traditional breeding, then the traditional breeding will be affected by the patents.

Although Siân Edmonds, the lawyer who was at the conference to explain the issues around patents, was–– remarkably––unaware of this, it is an issue that was very familiar to one of the panel members, Professor Cathie Martin. Martin is a scientist working at the John Innes Centre in Norwich who, for around 20 years, has been developing GM tomatoes.

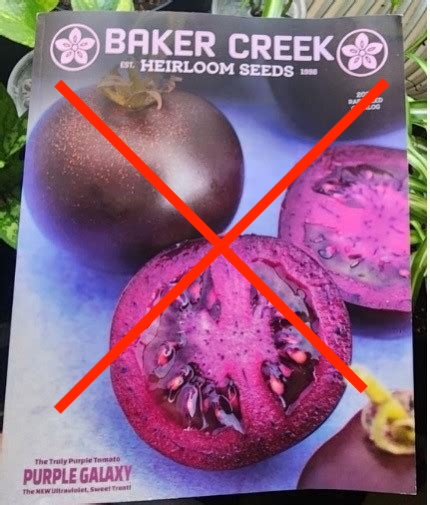

In 2024, the seeds of her purple tomatoes were sold for the first time, in the USA, by her company Norfolk Healthy Produce (NHP). Hot on the heels of the product launch was a patent infringement lawsuit against the Baker Creek Heirloom Seed Company, that was selling purple tomato seeds it claimed were produced conventionally. According to Baker Creek, tests of its tomato did not conclusively find evidence of NHP’s genetically modified material, but nor could it be proved that it was free of it. The Baker Creek tomato was withdrawn.

The European group No Patents on Seeds has sounded the alarm about companies using genetic engineering to reproduce gene variants and traits found in existing plant populations and claiming them as technical inventions, and then patenting them.

When asked whether she believed that the tomatoes she was developing could have occurred through traditional breeding, Martin answered: “Yes, absolutely.” She went on to explain: “We’ve actually got a project to try and screen for natural variants, having shown that we can produce them by editing.”

Martin and her team have two reasons for finding their genetically engineered traits in conventionally-bred varieties: firstly, to prove that they could occur through traditional breeding, and secondly to prevent them being produced through conventional breeding by threatening lawsuits. In doing so, they will secure the market, prevent the development of natural biological diversity, and lay claim to seeds that have been developed by our ancestors over millennia.

The real story?

It is GM Freeze’s suspicion that, given the apparent slim pickings that gene editing is currently able to offer in terms of products, the underlying business model for biotech companies is not that of selling seeds or food, but of breeding patents.

This article first appeared in the GM Freeze newsletter, Thin Ice, issue 69.